Public health errors 101: the basics

What they are, why they matter, and how we can learn from them

Why we should care about public health errors

Public health errors matter because they can affect entire populations, yet they have received surprisingly little attention. They may be rare, but there is much to learn from them. Such mistakes can undermine trust in health authorities, have different effects on different populations, and raise ethical questions about how decisions are made and justified. Studying them helps us understand how and why errors happen, improve responses when they occur, and strengthen prevention. For these reasons, examining public health errors is not only necessary but also a promising and exciting field of research.

The debate

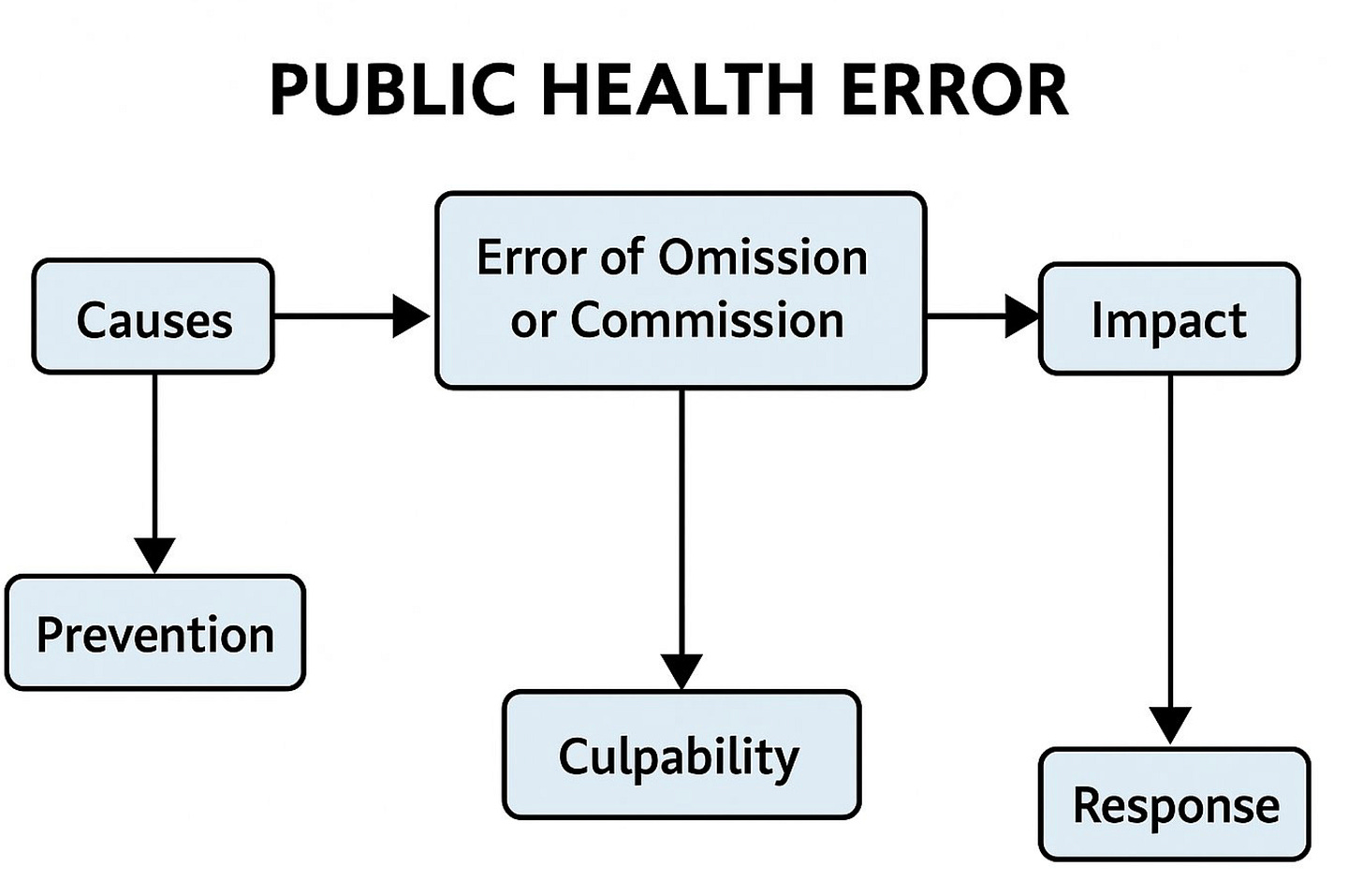

People use different criteria when trying to define public health errors. For example, must an error involve negligence or culpability (such as ignoring evidence or acting carelessly), or should intent to do harm be the guiding principle? Or should errors be judged only by their outcomes, regardless of what happened in the decision-making process? Is an error simply when the negative effects outweigh the positive? Does failing to act when action is needed also count? And what about degrees of error — how should we think about them? People tend to disagree on these points, and debates continue about whether errors must be culpable or not, as well as what the criteria for judging them should be.

Possible definition

In my own work, I propose a clearer, outcome-focused approach. I suggest that a public health error occurs when, in retrospect, a policy choice worsens public health. This decision must either cause direct and significantly greater harm to the public or fail to effectively prevent harm, compared to other available options.

I define a public health error as “an action or omission, by public health officials, whose consequences for population health were substantially worse than those of an alternative that could have been chosen, regardless of the causal processes involved in the consequences.”

This definition suggests that a decision is a public health error when a different decision would have enabled more people to have lived longer or been healthier. It also implies that both culpable errors and non-culpable errors should be considered as public health errors.

Based on those criteria, there are two broad types of errors:

Error of action. Interventions that directly caused harm to population health and were worse than doing nothing at all.

Error of omission. Failure to take action when measures were needed to protect the health of the population.

Errors of action

Examples of the first type include public health interventions and campaigns. For instance, public health campaigns in the 1950s using low-dose radiation to treat benign illnesses (that is, not for treating cancer), such as acne and ringworm. Children and young adults treated with radiation showed an alarming tendency to develop brain tumours, thyroid cancer and other ailments as adults.

Other examples include the approval of a faulty drug, like the drug Thalidomide prescribed to pregnant women in the 1950s and 1960s for the treatment of nausea. The drug caused irreversible fetal damage, resulting in thousands of children being born with severe congenital malformations. The painkiller Vioxx that caused heart attacks and strokes is a more recent example of an error of action.

Erroneous guidelines provide yet another example of this type of error. For example, a recommendation in the United States to give increased radiation doses to Black people compared to other populations during X-ray procedures (a practice called “race correction”). Another example is the recommendation to avoid giving peanuts to infants, which may have contributed to the rise in childhood allergies (adapted from The Conversation).

Errors of omission

The second category of errors includes instances of inaction or cases when public health officials were not doing enough to protect the public. For example, the failure to act against the harmful effects of tobacco; the delayed action to reduce child poisoning caused by lead paint inside U.S. homes; or the time it took for government officials to respond to the elevated levels of lead found in the drinking water of residences in Flint, Mich.

Health Canada’s delayed and inadequate response to evidence of addiction and misuse associated with the opioid OxyContin is another example of an error of omission (adapted from The Conversation).

The question of blame

Naturally, when the public is harmed, people want someone to blame, and culpability (such as acts of negligence or carelessness) often becomes our central focus. While understandable, this approach is misguided. Instead, I strongly suggest focusing on the consequences of public health choices — and the systematic factors leading to these outcomes — rather than on blame.

Doing so (removing blame) better aligns with the goal of public health, which is to maintain and promote the health of populations. In this sense, public health errors of action or omission are contrary to this aim: causing or failing to prevent harm to the public, whether they are culpable or not.

Causes

Public health errors are not just occasional mistakes; they often result from broader factors that cut across all types of errors, whether by action or omission, and whether culpable or not. We should assess the structural factors leading to negative outcomes, such as how science is interpreted, political pressure, and decision-making procedures. After all, the goal is to improve and learn from mistakes rather than pointing out blameworthy actors. Allocating blame leads to unnecessary politicization of the process and findings. Consider the following mechanisms (adapted from my JLME paper):

Ties between the government and industries (e.g., food or pharmaceutical industries): Agreements between for-profit industries and public health institutions can promote innovation (e.g., development of a new drug), but can also lead to public health decisions that favor these industries’ interests. It is often hard to identify such ties and the various ways they affect policy outcomes.

Agencies’ organizational structure: Public health agencies’ structure can favor one policy choice over another. For example, organizational structures that aim to limit one type of error (e.g., false positive) often leads to greater number of other types of errors (e.g., false negative).

Social assumptions of racial differences: Beliefs about racial differences can affect public health choices and recommendations. For example, in the in the United States, the belief that African Americans have denser bones and thicker skin and muscles resulted in larger x-ray doses to make diagnostic pictures. This belief and recommendation had appeared in standard x-ray technology textbooks until the mid-1960s. Consequently, Black Americans were getting increased radiation doses compared to other populations, which can have lasting negative health effects.

. Cognitive biases and constraints on information processing: Flawed human judgment and choice among policymakers can lead to poor policy decisions. A limited capacity to process information or systematic error in judgment can lead policymakers to make mistaken decisions.

Political considerations: Policymakers seek-ing reelection often overreact to voters’ opinions for credit-claiming purposes or underreact to avoid the blame associated with a certain policy.

These are just a few examples, and we should expect that combinations of two or more mechanisms often lead to errors.

Prevention

Once we identify a mechanism, we can start thinking about how to prevent the occurrence of similar mistakes. For example, problematic ties between health regulators and the food industry can lead to certain types of errors, such as erroneous guidelines. Finding the right relationship between the regulator and the industry can help prevent errors of that type.

Mistrust

My research found that mistrust is not tied to culpability. It often depends on which community is harmed by a public health mistake. We need to pay particular attention to the most vulnerable — such as marginalized populations — who in many cases already have low levels of trust in government. The effects of harmful policies on these groups can deepen and exacerbate mistrust in health authorities.

Response to errors

Mistakes are inevitable. We can work to minimize them, but we should not expect a world free from errors — even public health officials will sometimes get things wrong. What matters is how quickly and effectively we respond. Prompt action, such as revising guidelines, pulling a faulty drug from the shelves, or warning the public about harms, can save lives and rebuild trust. For example, in 1977 the United States launched a nationwide campaign to warn physicians and the public about the long-term risks of childhood radiation treatments. Communicating risks clearly and taking responsibility are essential for saving lives and maintaining trust.